Read below to learn more about

Westminster’s stained glass windows

The Life of the Christ: Scenes of Jesus’ Birth, Ministry, Death, and Resurrection

Jesus’ life has been a subject of artistic interpretation for generations, including in our own Sanctuary. At the bottom of the window sits the manger, shaped like an “X” and lined with hay. From the manger shines a blue form illuminated by a far-away star. Within the form is the familiar chi-rho (stylized like an English X and P)— the first two Greek letters of “Christos” (“Christ,” “messiah”). Above the manger is a baptismal font with a descending dove, reminding us of the presence of the Spirit at Jesus’ baptism. The water below the font recalls the Jordan River, where John the Baptist baptized Jesus. The third panel depicts a bundle of grapes, a stalk of wheat, a chalice, and loaves of bread, all symbols imbued with meaning at the Last Supper. The bread is divided into twelve segments, recalling the twelve who dipped their hands with Jesus’ at the Last Supper. Chronologically, the crucifixion follows in the panel above, with three crosses, the central (purple) cross encircled by a crown of thorns. Above the crosses is the empty grave, a symbol of resurrection, marked by the flag of victory, to remind worshippers of Jesus’ final defeat over death and despair. The apex of the window once again returns to the chi-rho, a reminder of Jesus’ ascension, depicted in the book of Acts.

Jesus’ Parables: Unpacking Stories about the Kingdom, Faithfulness, and Responsibility

The parables of Jesus are among the most memorable scenes in scripture. The peak of the window depicts the chi-rho, a common symbol for Jesus, atop a hill, with lights flowing from the letters. The setting is meant to recall the Sermon on the Mount and its attendant teachings. Below the lights a hand holds a brilliantly shining coin next to a broom and candle, reminding us of the woman who searched to find her lost coin in Luke 5. A shirt, scissors, a needle, and thread remind us that new patches can’t be sewn into old garments, and the broken jar, from which wine pours, reminds us that new wine can’t be poured into old wineskins, all prominent images Jesus uses to describe the newness of the Kingdom of God in Luke 4. The mustard plant is centered in the window to remind us of the mustard seed (Mark 4), below which another hand gathers fish from a basket (Matthew 13). Coins and a shovel represent the parable of the talents in Matthew 25, and finally the lamps, both lit and unlit, call us to remember the bridesmaids in Matthew 25.

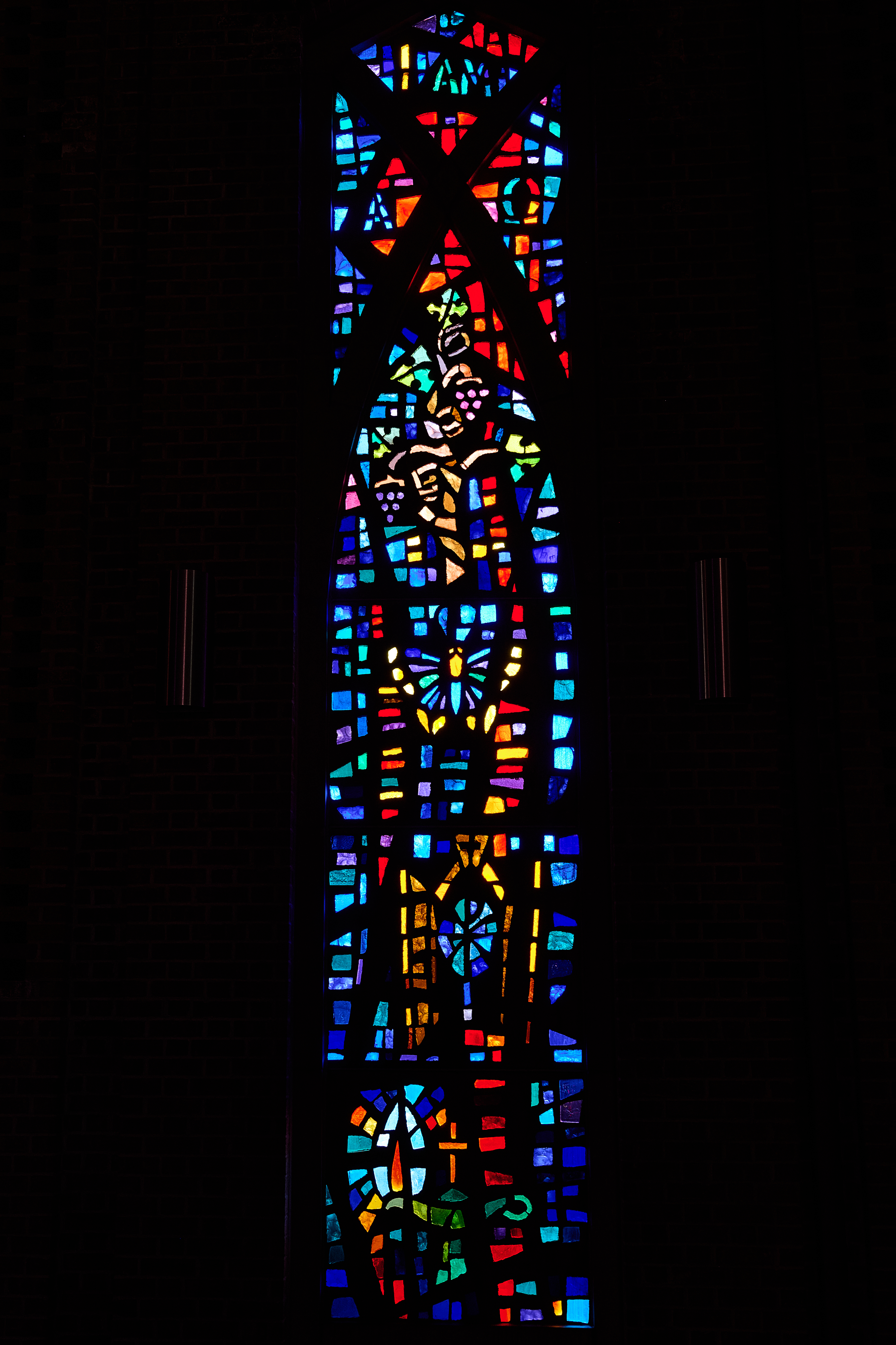

Jesus’ “I Am” Statements: Understanding Who Jesus is Through Common Images Imbued with Special Significance

In the Gospel of John, Jesus uses a series of metaphors to describe his identity and intentions, all introduced by the greek “Ego emi” or “I am,” words inscribed in the apex of the window in shining yellow and teal. Below “I Am” are the Greek letters Alpha and Omega, the first and last letters of the Greek alphabet, reminding us that Jesus utterly encompasses all creation. “Alpha and Omega” is the only statement not found in John (Revelation 1:8). Below the Greek letters is a grape vine, from which disciples grow as branches (John 15:5). In the center panel, the butterfly emerges from the apparent death of the chrysalis, a clear symbol for new life, reminding believers that Jesus is the resurrection and the life (John 11:25). A door opens to the “chi-rho” below the butterfly, a reference to two of Jesus’ “I Am” statements. Jesus is both the door — literally depicted here with the familiar chi-rho symbol (John 10:7), and the way (John 14:6). Toward the window’s base is an oil lamp that radiates light, a bold proclamation that Jesus is the light (John 9:35). In the second panel fish and loaves are abundant, a reminder not only of Jesus’ feeding the great crowds, but of his identity as bread of life (John 6:35). Finally, a star surrounds a lamb, the good shepherd as the foundation of the window (John 10:11).

Genesis: God in Creation – Representing God’s faithfulness in Creation and Recreation in the Hebrew Scriptures

One of four smaller windows, the Genesis window retells the first stories of Scripture, and reminds us of God’s generative work in creation. From the top of the window a hand reaches down, unspooling stars and sun, planets and waters. The universe begins to mingle with known creation, as birds, fish and mammals appear, and humans, naked, walk among the created vegetation. Full of color, the window depicts creation without conflict. God said it was so, and it was. Finally Noah’s arc and the symbol of God’s covenantal promise, the rainbow, shine through with light, reminding us of God’s faithfulness and the promise to never again bring destruction to the good creation.

The Prophets: God Speaks – Depicting God’s Faithful Challenge to God’s People Through the Voices of Prophets

In the time before the Messiah, God spoke to creation through the prophets. These Hebrew texts are among the most evocative in Scripture, from the well known symbol of the mighty fish associated with Jonah we move up toward Isaiah’s hot coal. Above the whale is the symbol of Amos, the prophet of God’s righteousness and justice often quoted by luminaries such as Martin Luther King. Amos is depicted by a plumb line and weight that cuts across three panels. In Hosea, God is imagined to be Israel’s bride, thus Hosea is represented by the wedding rings and covenant of the second panel. The story of Daniel, which reminds us of our fidelity to God above all other kings, is depicted in the fiery furnace, from which smoke rises, even as those within are protected by God. Ezekiel is rendered through the city gates of Jerusalem, above which we recall Jeremiah’s plea that God’s word be written on our hearts. At the peak of the window a fiery piece of coal held by tongues reminds us of the hot coal that burned Isaiah’s mouth, purifying him to receive God’s word.

The Hebrew Bible: God Called Men and Women to Do the Work of the Kingdom Well Before the Time of Jesus

Once overlooking an outdoor garden, the Hebrew Bible window now enclosed between the Sanctuary and Atrium. In the Old Testament window we find Moses and the burning bush, from which he received the divine commission and the divine name (“I Am”), a sheaf of wheat to remind us of tenacious Ruth, the grandmother of David who gleaned on Boaz’s fields, the horn and clay jars of Gideon, the great judge before Israel, the jar of oil Samuel used to anoint Saul and David, and the harp associated with David, the humble shepherd who rose to become Israel’s greatest king.

The Psalm 23 Window: Exploring One of Scripture’s Best Known Texts

A later addition to the Sanctuary, rightly nestled between the transept organ pipes, the Psalm 23 window recounts one of Israel’s best-known songs. The chi-rho at the top of the window calls us back to Jesus, the great shepherd, in whose house we dwell (the door and steps welcome the viewer into God’s house). God’s goodness and mercy and the shadow of death are dually depicted by the sun and lightening bolts, and the overflowing cup of blessing which the narrator praises, is depicted by the wine and doves. In the center of the window is David — by lore the author of the Psalm — with his harp. The window is anchored by the sheep, a reminder that we are led and guided by God the shepherd.

The Early Church: Depicting the Gospel’s Global Reach Through the Early Saints of the Church

God has remained active in the world throughout the ages, and in both the Reformation window and the early church window, we are reminded of the many ways God sustains history and nurtures the church. Reminding us of the great commission in Matthew 28, the bottom panel of the window depicts a cross over the globe and the purifying waters of baptism flowing from a shell. Directly above the shell we see the dove, an image of the Spirit, and tongues of flame, recalling the first Pentecost, when the Holy Spirit moved among people of all nationalities gathered in Jerusalem. In the center of the window, a sword pierces Scripture and the latin “Spiritus Gladius” (sword of the Spirit) radiates from the page. The image is taken from the Apostle Paul’s description of the armor of God in Ephesians, and reminds of the tremendous theological output of Paul. Above Paul’s sword is a burning heart pierced by arrows, an early symbol associated with Augustine (d. 430ce), whose heart “burned” within him on the road to faith. Indeed, the Augustinian heart burns with love for God and others, and is pierced by the word, which calls us to greater Spiritual growth and finally, in finding truth, finds its rest. The Latin “Veritas” recalls the early saints and their quest for divine truth. The lion and lamb lie in a pastoral scene with birds and bountiful gold, depicting St. Francis of Assisi (d. 1226ce), who is often associated with his love of nature and his charity toward others. Through these windows we have seen the gospel spread from Jerusalem to Africa and, with Assisi, Italy. In the penultimate panel we move Britain, where the Celtic cross, representing St. Columbia (d. 597ce), the first missionary to the Celts in Iona (Scotland) is centered. The crown and palms at the peak of the window recall the many other unnamed saints throughout history who died for their faith, and whose victory is secure in the resurrection.

Reformation to Present: God’s Continued Call, From the Reformation Through Scientists, Teachers, and Everyday Saints

As with the Early Church window, here is depicted the activity of the Spirit after the life of Jesus (and indeed reaching into our lives today). The window moves from the early Reformation in German to the modern era. Anchoring the window is the Luther Rose, recalling the great Reformer who powerfully protested against the institutionalized church with the posting of the 95 Thesis on October 31st, 1517 in Wittenberg. Above the Luther Rose is a hand holding a heart, a symbol associated with John Calvin, the father of Protestant theology. Calvin’s motto, “My heart I offer you, Lord, promptly and sincerely” is well summarized in the symbol. The third panel recalls the origins of the Presbyterian faith with the thistle, the national flower of Scotland, home of John Knox. Central to the widows is an open Bible, upon which sits a globe with a cross above it, meant to depict the many who have gone out into the world carrying the word of God, and whose work links them to the oldest matriarchs and patriarchs of faith. Modernity is represented in the upper panels by a number of vocational symbols. A chemist’s beaker sits in a three prong stand next to the caduceus (medical staff), to remind us that science and faith are not in conflict, and indeed the gifts of the mind are a gift of God. A lyre (harp) represents the arts. The tools of labor coexist with the image of an atom, reminding us of the goodness of work (and of perennial concerns of the mid-20th century, at which time the windows were designed), and of God’s sustenance over the smallest particles of our existence. A lamp represents the illuminating work of educators and lawyers and a compass the work of engineers and architects. Finally, with the boat and cross, there is the seal of the World Council of Churches, whose goal is to connect Christians across the globe. The Greek word “oikoumene” (“inhabited earth”) sits above the seal, a forceful proclamation that all in the inhabited earth belongs to and is sustained by God.